The Human God

Telling the story of the God who is one of us, and with whom we are one, in paintings.

What religious person of the ancient world would invent a story in which the Creator is born in a scandal involving an unmarried teenage mother, born without privilege, and laid in a feed box?

The shepherd’s witness to God’s humble, vulnerable humanity confronts and dismantles our expectations, looking (as we too often do) for a God who meets human aspirations of power and prestige.

Mary is as baffled and quietly grateful as we are; that God chose her, that he sides with humanity permanently against all who oppose us, even our own hatred of ourselves.

At the end of a long season of bearing, at the end of a long journey, at the end of a long day and after excruciating pain, after holding him close to her heart, she stops bearing God for the first time since she said to Gabriel “let it be.”

She lays his bright flesh in a feed trough, swaddled against the anxiety of leaving her womb, nestled by wool and straw from the cold night’s sting.

The One who was God before all worlds lies there, as helpless against fragile existence as any of us, bound to the poverty of homelessness, a slave now to the elements he created, a hungering creature of necessity, soon to be an immigrant fleeing political terror, held aloft from the damp ground by wood that as God he holds together.

At the dedication of the Temple, Solomon said of this tightly wrapped bundle of dust, “the heaven of heavens cannot contain you.” Yet contained he was for nine months within this weary teenager, smeared with dirt, sweaty from her labor, catching her breath in time with this baby, the One who in the beginning breathed the stars into the astonished sky above them.

The beginning and end of the Christian revelation of God, of all that Jesus does for us and for our salvation, is this baby, this mother, this dust, this sweat, the wood of this feed box, prefiguring the wood of his cross.

God takes the form of a baby because divine helplessness is greater than any other force in the universe.

When we encounter the smallness and poverty of this human child, God is not becoming something that God is not but revealing to us what it means to be the hidden God from eternity. Can be as small as God wants and his love anyway prevails.

His poverty is what holds all things together, sets all things in motion, gives life and light, divine energy and breath, to all living things. His perfect love casts out fear.

“Do not be afraid,” the Angels tell us still. This gospel is good news for everyone because God is revealed as one of us, who is with us and for us—the human for all humans in whom all humans have light.

When on the first Christmas divine humility and poverty are revealed as the foundation of all that exists, this revelation of God in the weakness of flesh threatens all human notions of power, all conquering that rests on exertions of might.

The real Christmas was and remains political…and dangerous. The conception and birth of Jesus—the now-speechless infant who in the beginning spoke all things into existence, a helpless child who can do nothing but lie there in hidden glory, the government of the cross resting invisibly on his tiny shoulders—sets a challenge to all leaders and governments, visible and invisible.

Temporal rulers are bested here by this helpless infant, by an eternal Wisdom of others-directed, self-sacrificial love that does not seek its own, that does not keep a record of wrongs, that is not jealous, that seeks to serve rather than to be served.

Herod knew the jig was up, that the age of self-seeking rulers was now exposed, that the game was over. Herod turns to murder to try to reimpose the old order.

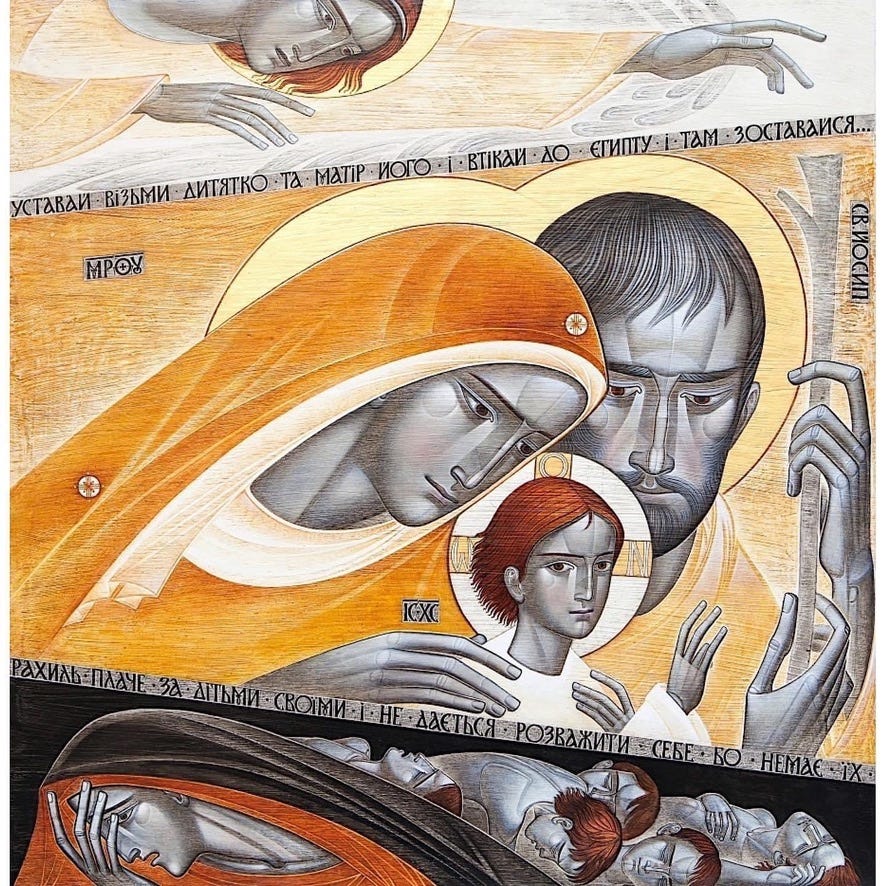

The Ukrainian iconographer, Lyuba Yatskiv, captures the horror real boys and real mothers faced in the aftermath of the real Christmas, the infamous slaughter of male Hebrew children in and around Bethlehem that we remember every year on the Fourth Day of Christmas.

Those desperate to hold on to a false authority that’s always threatened by divine humility lash out, for violence is their defeated way of maintaining strength. God answers—then, now, and in the future—with the surrender of a world-converting cross.

What the powers did not know is that in killing these children and (eventually) killing Jesus Christ they robbed all violent actions of their permanence. Violence has no future because of this infant God.

These children and all who suffer violence now have in Jesus Christ a glorious way to endure beyond suffering and death, to shine forever in the kingdom of their Father, while the kingdoms of darkness and their violence await shameful expiration.

The Love that is God never fails but not because Love always triumphs. Love’s patient victories often fall on the far side of horrific defeats.

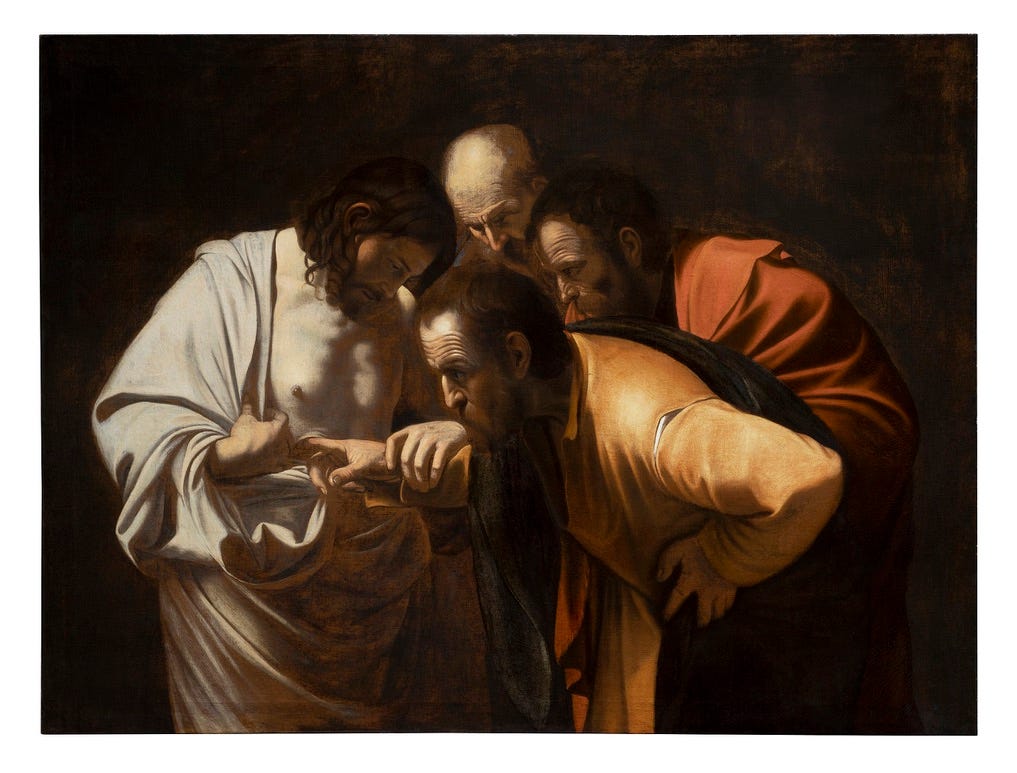

The humanity you share with Jesus Christ is seated next to the Father, forever bearer of Mary’s DNA with a yet-beating heart and wound-marked hands with which to embrace us and—we should not forget this—memories of his life with us as one of us:

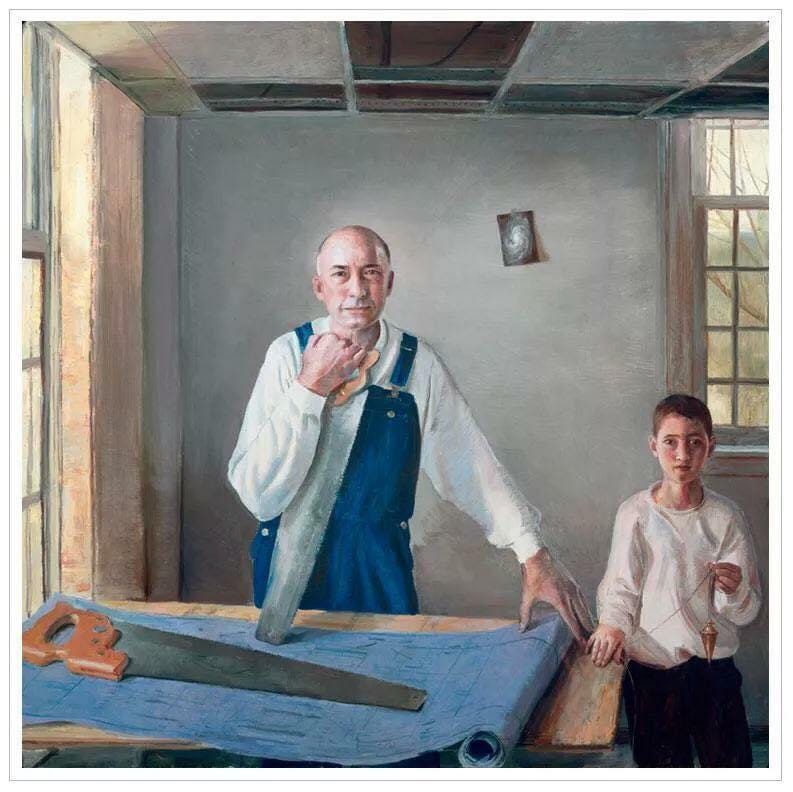

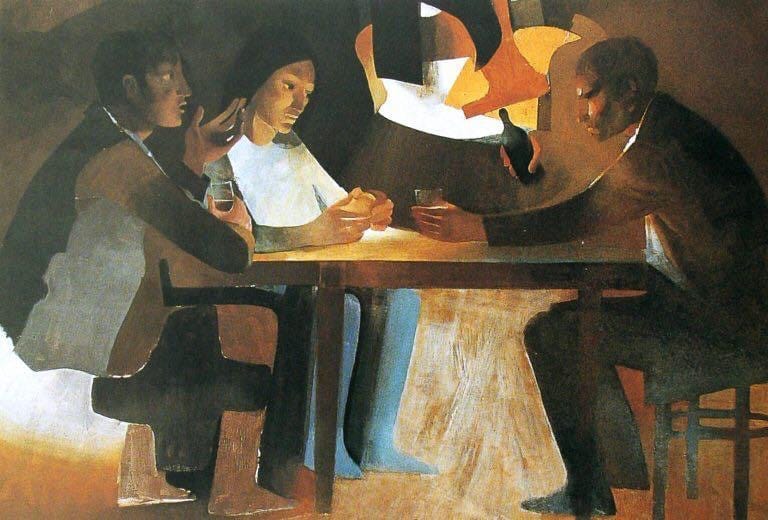

Memories of home-cooked meals and frigid desert evenings. Sawdust memories of hard work and sweat. Recollections of wine and friends and laughter at midnight. He made our sometimes brutish but (somehow also) beautiful existence his own and did not spare himself any of our sleepless small hours, our helplessness in the face of the suffering of children, our hunger for bread, our world weariness—this endless, gnawing awareness of contingency—and our bone-tired aches at end of day.

The Incarnation means that God gets sawdust in his eyes and dirt under his fingernails, as Jesus sets to work with his carpenter stepfather in the same world he made together in the beginning with his divine Father, crafting with Joseph ordinary household things from the same materials he as the Word from before all ages spoke into being, like the blueprint of that galaxy on the wall behind them. As sons and daughters of Mary—for if Mary bore Christ and we are all “in Christ,” then Mary bore us also—we are all of us called to this co-creative work.

Jesus spends decades in obscurity, hidden, as most humans are, working, and living, and celebrating and suffering in anonymity and silence, and this too is the way it is with God. Like the best waiters at table, he does not draw attention to himself even as he takes care of everything without us noticing.

Eventually, after much absence, Jesus walks a dusty path and arrives at the Jordan.

There, among the tall reeds on the bank stands Jesus, who has just walked from Nazareth—that out of the way, one stoplight village of nobodies of whom no one expects anything—his feet tired, sore, and dirty.

Jesus wades in ankle deep. The cool, flowing water is soothing. He watches his human brothers and sisters descend one by one, waist-deep, faces drawing near to John the Baptist.

They are entering the water to be cleansed, to repent. Jesus has no need for the cleansing, or the change of heart and mind, and yet here he is, his human face set toward suffering encounter.

Bonhoeffer says that Jesus does not ponder his perfection or feel his superiority but rather expresses solidarity with everyone gathered to be made well, to amend their ways, by—what wondrous love is this?—presenting himself for baptism, too.

As he approaches John, the Baptist recognizes not only the body of his cousin, with whom he played as a child, but Isaiah’s lamb, the One who takes away the sin of the world.

John is reluctant. He does not see why Jesus needs this ritual because he does not see the cross in this watery moment, does not understand that Jesus is already, here in the murky waters of the Jordan, descending into chaos, darkness, and death, taking on himself the sin of the whole world.

This is not a God who remains on the banks of the river, uninvolved and aloof from the pain of existence, but who joins us in our predicament, bears one of these bodies infected with death.

Unlike the others gods we project and handcraft and make wishes to, and negotiate with for fortune and fame, this God is a baptized God. He identifies with us so that he might identify us with him. Jesus wants us to be human as God is human.

Unlike the children of Israel who walk across on dry land, Jesus goes down under the water to be with the armies of pharaoh, and with those taken by the great flood, and to bring us all back with himself from the depths.

The baptism of the human God does not separate Jesus from any other humans, nor any humans from any other humans, but draws every human into the triune fellowship of love. Jesus is baptized to be in intimate solidarity with every human.

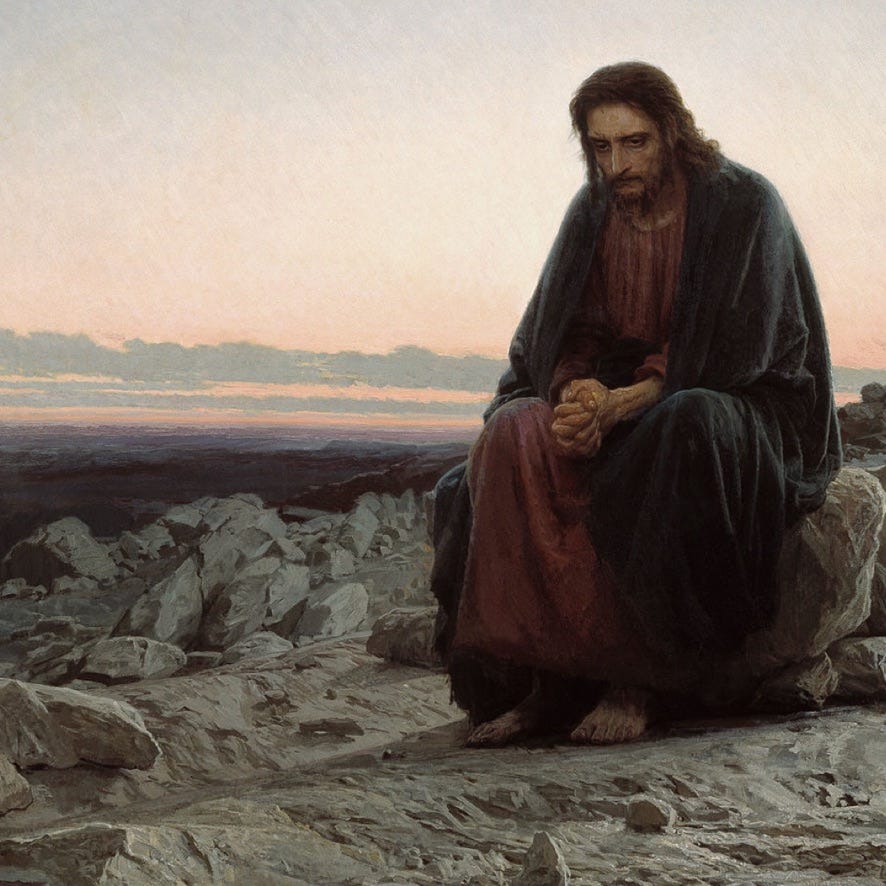

Then sent into the wilderness by the Spirit, Jesus is cajoled by satan to leave the limits of existence, to do magic tricks, to defy nature.

It’s tempting to remain at the surface of the gospel accounts of the wilderness experiences but at their core satan’s enticements are invitations to Jesus to stop being human.

None of us can make bread from rocks and none of us can fly without external aids, and Jesus is exactly one of us in all the limitations humans share.

Jesus is not Superman. Jesus is not Merlin.

Remaining human, accepting limitations, binding oneself in humility to created boundaries is a sacred vocation.

Jesus is the Word through whom the Father spoke all rocks into existence—all orchids, all stars, all things that fly, and all things that are a delight to the eye and good for food.

Jesus is the human God who calls all things into being, and protects them in their existence precisely as the things they are.

Jesus could of course have made bread from stones but not without ceasing to be human. And not—this might surprise—without ceasing to be God.

When we stay with these wilderness encounters awhile we begin to understand that Jesus remains not just human in the exchanges with the devil, he also remains divine.

The sort of gods we project, whether in ancient lore or in our contemporary cinematic universes, are the sorts that wield “powers” to control persons or outcomes, personas who might change the nature of things or trespass boundaries to suit their ends, but they are not the living God revealed in the Scriptures.

In Jesus Christ to stop being human is to stop being God, and to stop being God is to stop being human, because in Jesus Christ there is no separation between remaining human and remaining God. In him they are one and the same thing.

Ponder with me for a moment the mystery that we have entered when we encounter Christ in the Gospels:

When Jesus is on the Sea of Galilee with the disciples, and storm winds and waves frighten even seasoned fishermen, we find the God who made the waves, the wind, and the wood the boat is crafted from—who made everything and holds everything together—tired and asleep in the hold of the ship.

God is asleep on a boat, even though our first thought as readers is that Jesus, a flesh and blood human, needs a nap (and that is true, too).

When the disciples awaken Jesus and he surveys the situation (and their hearts), he rebukes their fear, and then a human stands up on two feet in a vessel sloshing with lake water and speaks: “Peace, be still.”

Someone just like the rest of the disciples—with breathing lungs and a beating heart, sleepy and finding his sea legs—makes the wind stop gusting and turns the waves to glass with his words. As readers, we think Jesus is God and this awe-inspiring ability fits his divinity, but Jesus is also flesh, no more special in his biochemistry than anyone else in that boat on a sea gone wild. He is both Lord and servant of the sea, and it his humility, his words—perhaps spoken in a “still, small voice”—that the winds and waves obey.

Being a servant is not a temporary way of life for God; it is subversively permanent. We struggle to imagine this is who God is among us and for creation. But once the penny drops, you cannot unsee it: Jesus is the overthrow of everything.

Jesus is the name above all names because the One who serves all things in creation is at once the revelation of what it means to be human and what it means to be God. The ascension that follows his elevation by the cross, shows that God’s very nature is to be our steward.

Some teach that a temporary humility of Jesus leads to a “greatness” that makes him like any other earthly king, only one with the sort of infinite power that fallen human imagination expects. In this scenario his “humility” leads to eternal tyranny. But the angels that appear after Jesus ascends tell us that the same Jesus who ascends is the same Jesus who returns.

It turns out that the “zeal of the Lord of angels” Isaiah speaks about, the zeal that accomplishes the making well of the world, is a profound vulnerability that does not seek its own.

If you would meet personifications of God in the world spend time with janitors and waitresses, with nurses and firemen, with doormen and air traffic controllers.

Power is a great temptation. The desire to be like those whom we are tempted to consider powerful can lead to self-deception, and is the surest way to forget that God is the Gardener we executed, the Shepherd we forsook, the Physician we rejected, who yet loves us and the world.

The human God is among us as the child whom he must become, as the servant: “I am among you as one who serves.”

Jesus reveals God as poor. Jesus is born of Mary into a carpenter’s household, birthed in a cave or shelter with other earthen creatures and their shit, and not in a place where the wealthy of the time dwelt, not only as a judgment upon the ways in which we exalt ourselves with positions and wealth but because his coming in this way discloses something to us about God.

If he had come among us as a human of status or influence or strength we would have a misapprehension of who God is.

”Since a divine Spirit inhabited the body [of Jesus], his body must certainly have been different from that of other beings, in respect of grandeur, or beauty, or strength, or voice, or impressiveness, or persuasiveness … whereas Jesus was, as [the Christians] report, little, and ill-favored, and ugly.” —Celsus

Celsus was an ancient Roman critic of the church and its gospel. Seeking to hinder anyone who might be attracted to Christian faith, Celsus argues that the church’s story is impossible. After all, smart and sophisticated humans look for signs of divinity in physical beauty, charisma, and stature.

If the invisible Spirit that gives all things life and movement were to join itself to human flesh then surely, Celsus says, that person would look like our projections of divine and human strength…someone like Adonis or Zeus.

We presume only the ancients thought this way but look at the “gods” we have assembled in, for example, the Marvel Cinematic Universe. They are handsome, fit, strong, resourceful practitioners of disciplined, old school aggression. If they’re not endowed with cosmic powers, or the capacity to harness nature in some unique way, they’re super intelligent with sophisticated technological exoskeletons, or trained experts in mystical or martial arts.

Superheroes are easy on the eye, clever, muscular, and violent.

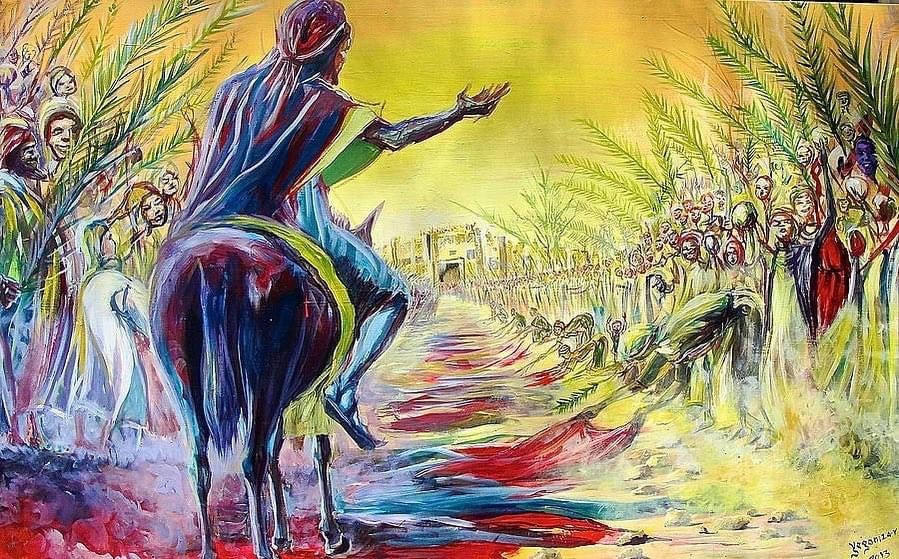

The human that rides into Jerusalem, the God that approaches the Eastern Gate on an ass, relies on no such powers.

The weakness of Jesus Christ, the vulnerability of humanity and divinity that meet in his unique Person, is stronger than our notions of power.

You can’t see that by looking at him.

Humanity’s actual God is not an alien humanoid like Superman, impervious to harm, but someone who bleeds and sweats, who endures ridicule, torture, and crucifixion.

Short of stature or not, we know Jesus wasn’t striking. He didn’t standout. He was despised and in the end, in his death, he was as Isaiah tells us disfigured beyond recognition.

Let this mind be in you which is also in Christ Jesus, who took upon his eternity our every disability, who lived among as a servant, who goes silent to his execution, so that the world might live.

When Jesus wraps a towel around his waist and washes the feet of his disciples he gives us a portrait of the unseen Father, who holds all things together—visible and invisible—as an unassuming, humble servant.

When we dare to mess around with the invisible structures by which God holds the visible world together—splitting atoms, for instance—we witness the awesome energy generated by the smallest (unwise) manipulation of his handiwork.

Yet this incalculable energy—even the smallest fraction of it leaves us in awe—is harnessed to an extreme humility.

What this moment at the last supper reveals, what this washing of feet shows us, is that the power of God has its origin not in what fallen human imagination supposes—not in great demonstrations of might, of subatomic or interstellar power—but in innumerable divine acts of indiscriminate, behind-the-scenes stewardship.

He literally cares for all things, great and small, from what may seem useless to us—the things we would throw away—to things of such exquisite beauty we are left without words.

God is the great janitor, kneeling on the floor of the universe, towel in hand, ready to do the menial work that holds all things together, the work of a love that does not seek attention, does not boast, is not rude or jealous, that keeps no record of wrongs, that does not fail—the measure of the love with which Jesus loved us and with which he commands us to love each other.

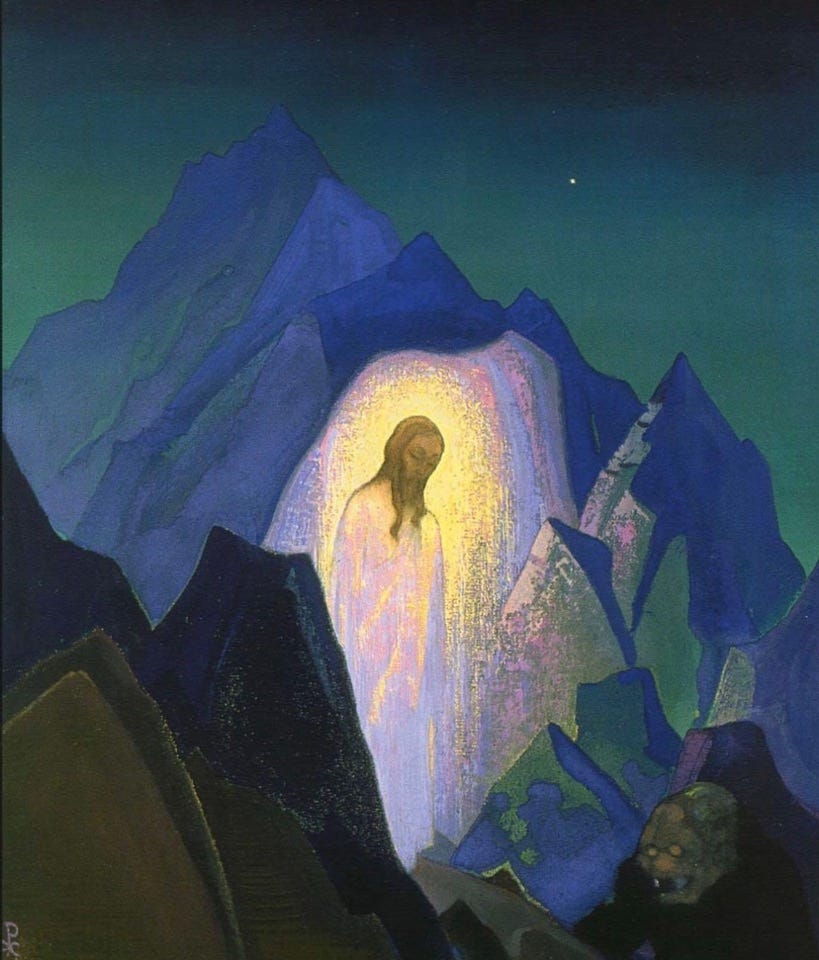

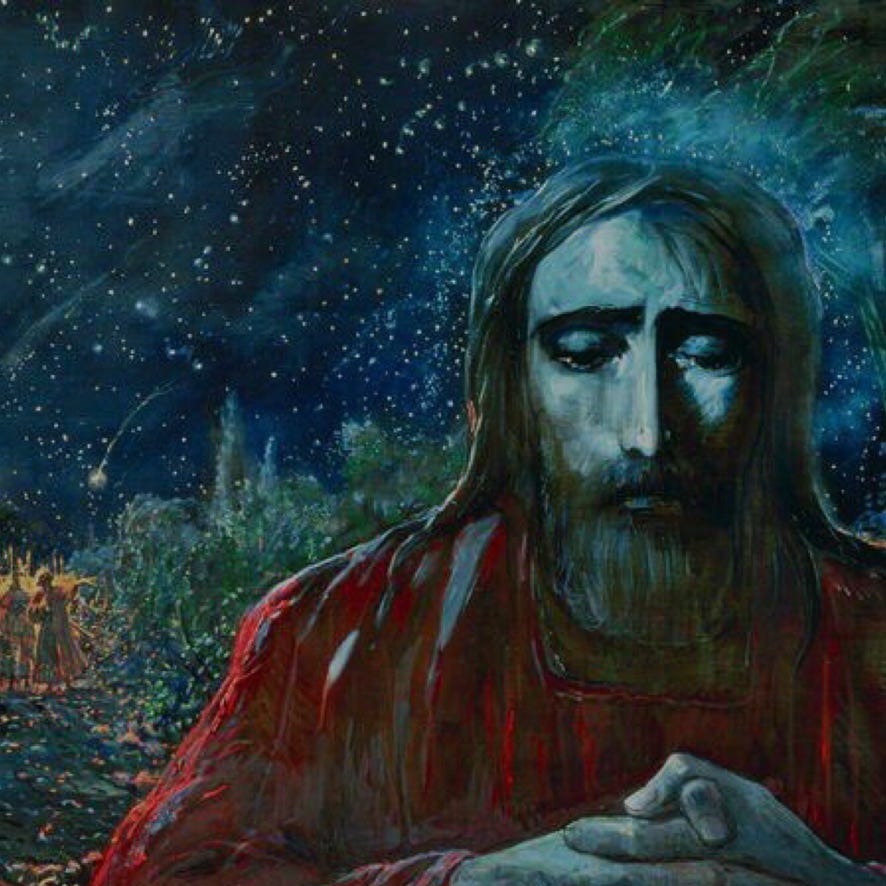

About a dozen years before my stepfather died, he had a vision of Jesus while kneeling in the crypt of a church in Rome. He said that a wall in front of him became translucent, and that through the wall he could see into a garden.

Jesus was there, on his knees, his robes a bit muddied from kneeling. And he was praying. After a while he asked Jesus why he was kneeling in the mud. Jesus said: “This is where I always am, praying for the world.”

Dad was a bit of a mystic, but this encounter always felt like the most authentic experience of Jesus he reported having. It still does. I still ponder it from time to time. It rings authentic.

“When Christ came into our midst to redeem us, he descended so far that after that no one would be able to fall without falling into him,” writes Hans Urs von Balthasar, in his Heart of the World.

Johann Baptist Metz says “Satan wants to make Jesus strong, for what the devil really fears is the powerlessness of God in the humanity Christ has assumed.”

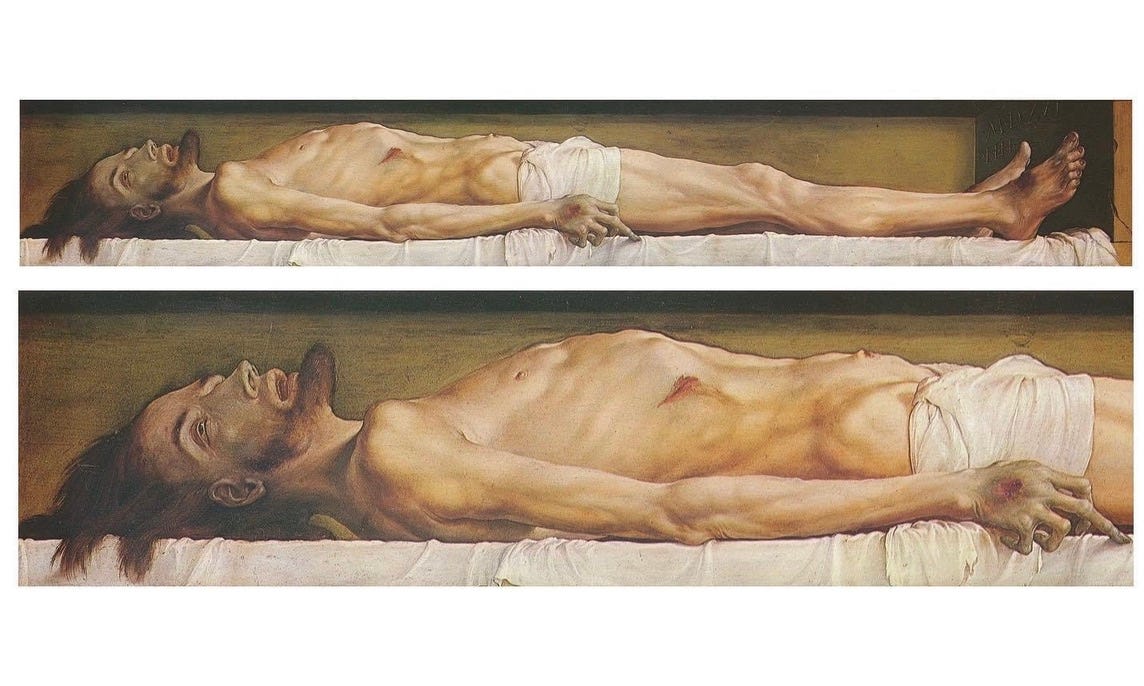

If this is true then the dead body of Jesus, lying still in the grave, is the undoing of the devil, and the end of death, however hard that is to imagine.

No matter how far humanity falls, or any person falls (for we are all inseparably bound as humans to one another), we land on the dead body of Jesus, who dies to make this so, who dies to arrest our descent into non-existence by putting his dead body under ours.

You see, the dead body of Jesus—remember, we did our worst to him, he is in the tomb “marred beyond recognition”—is not at odds with what it means to be God but is somehow a startling revelation of what it is to be God from eternity.

This dead body is God’s. This dead body is what it means to be the Creator and the one who in patience and humility serves in love what he creates. And so we should never refer to the dead body of anyone as if that is no longer the person lying there, for we and the God who is human are inseparable from our bodies.

The mystery the human God reveals is this: the true giver of life, who gives life to all things, who alone loves all the things he makes, accepts the condition of actual death in order that all things might have his kind of life.

From his stillness in the grave, from what looks like the end of all things, a new creation springs to life in us and in the world. There is nothing more life-giving or converting or transfiguring than to at long last fall into the arms of God.

When we land on the dead body of Jesus we also rise and ascend with the human God as he rises and ascends—bodily!—freed not only from this broken existence but also unchained from our finitude, as with the whole creation we are born anew into the divine permanence God desires for us all.

“I, your God, did not create you to be held a prisoner in hell. Rise, let us leave this place, for you are in me and I am in you; together we form only one person and we cannot be separated,” wrote one of the first Christians whose name is now lost to history but not to God.

Our bodies are deeply important and inseparable from us because God has a body exactly like ours, a body that died, a body that was prepared for burial, a body that was entombed, and a body that mourners attended to, wept over, and laid in the ground with their own hands and hearts. And that body is now risen, however transfigured for eternity, and is ascended into what it forever means to be God.

My friend, Paddy Lynch, a mortician, has taught me a lot about dead bodies. He says that they are, like newborn babies, the most vulnerable of humans, and what we do for the dead in their death is the highest form of corporal mercy, or mitzvah, we can perform. Why? Because the dead cannot do anything for us, are beyond returning the mercy.

At Lynch & Sons, they treat dead bodies with tremendous dignity, caring for them as intensely as infants, because they are as or more vulnerable (infants do not remain as vulnerable and often eventually return some of the mercies we bestow on them); also because dead bodies are, among the living, signs of the resurrection.

When we are dead God is finally able to do something with us, can finally redeem everything about us, because we can do nothing to resist his saving work. As one Scottish undertaker told my friend, Eric Peterson, a cemetery is ground that belongs to God—“God’s acre,” he called it—and “within it are buried the seeds of resurrection.” Our dead bodies sow into the ground the eventual renewal and permanence of the cosmos, and will in the end cause all things and all persons to be renovated and made eternal.

For, as Paddy’s uncle, Thomas insists, and as Cyril of Alexandria taught, the Spirit does not raise the idea of Jesus from death but his body. It is not the memory of Jesus that is enthroned in heaven but the eternal and human person we encounter in the gospels, whose crucified and resurrected body the Spirit knit in the womb of his mother.

Jesus lives on in the selfsame flesh Mary gave him at the right hand of the Father, wounds and memories and all.

Again, if the body of Jesus remains the body of God in his death, and that body is somehow the body that leaves the tomb and appears to Mary Magdalene—even if after the resurrection the body of Christ has the ability to be in many places and persons, in many mysterious ways—we want to resist saying that the dead body of any human isn’t that person anymore.

Jesus is resurrection and life. And we are members of Christ. And are seated with Christ in heaven. There is one person who contains all others, who contains all worlds. We are because of this reality already the aroma of resurrection life everywhere we go even before we die.

Our lives should be fragrant with eternity.

We are the ones in the world who call brothers even those who hate us and forgive all by the resurrection.

- a remarkable piece of writing. - so very special. - perfect alignment of words. - every word appears essential. 🐑👑🙏

I just loved reading this. There is so much to enjoy here - and to remember - because it is true and Biblical.

This is beautifully written, and it is good to know that I can read it again & again.